Lisa M. Lane wrote a elegant post on Three Kinds of MOOCs on her blog the other day, and it has me thinking and reconsidering. She organized current MOOCs into three categories: Network-based, Task-based, and Content-based. The brilliant part of this classification scheme is that all three principles (network, task and content) are part of all three types of MOOCs; it is just that each type has an emphasis on one of those principles.

Why do I like this? Because it is at the heart of my attempts to adapt MOOC elements into my courses. As I've said before, the MOOC is just a stepping stone. It provides us with a new educational paradigm. Not all courses have to be massive or open to take advantage of the ideas that have been sparked for the MOOC. I also contend that the MOOC is not for all people or learning levels. With Lisa Lane's classification, I need to refine the last thought a little.

The network-based MOOC has an emphasis on the evolving conversation and learning networks, and is indicative of the first generation of MOOCs. My thoughts regarding the level of the learner/student is most focused on this type of MOOC. Last week's #MOOCMOOC seemed mainly focused on generating conversation, even though there were tasks involved. The building of a learning network was critical. But this type of MOOC requires some level of understanding, life experience, and intellectual maturity. The full format does not work well with most undergraduates, especially when you are trying to help them build up the mental framework of a discipline. Putting a Freshman into such as situation would only add disconnections (but this may well change in the future).

The task and network-based approaches are more in line with helping students build up their intellectual strengths. This is where I'm focused. Adapting the tools and principles of the original MOOCs to build courses that help students tackle content, build mental frameworks (content in context), and recognize the importance of the learning community/network.

Now, I would not call what I do as MASSIVE. First, I'm really bad at publicity, so most people don't know about project BOLO. I do want the course and materials to be open, because having other people come in adds perspective to the discussions. My primary focus though is going to be the students I have in class (I will comment to everyone, but my commitment is to those enrolled in the campus course). These are reasons I see what I'm doing as based on MOOCs, but not an actual MOOC.

This blog is a diary of my thoughts on teaching and learning, educational models, and teaching techniques. This is more than pedagogy, or andragogy, but goes my thoughts about how we experience and learn.

Welcome

This blog was started as my reflections on the 2011 Change MOOC. It is now an on going journal of my thoughts on Higher Education, specifically teaching Biology.

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Learning Objects and MOOCification

During #MOOCMOOC last week, someone coined a new phrase (at least for me): MOOCify. Basically the idea of turning a current class into a MOOC.

While I love the term, I'm not crazy about the underlying concept. It's not that I don't think it can be done, and it is not because I "distrust" MOOCs.

The reason I'm not crazy about the word MOOCify is that it misses out on a critical point: the MOOC is not for all audiences. Instead, I would rather talk about adapting the MOOC model. More specifically, I talk about taking the connectivist foundation of the MOOC, and the tools commonly used in a MOOC, to build a stronger (and more distributed) learning community revolving around a class.

Let me break my thought down using my class as an example.

To start with, the class I'm talking about is a College Level Freshman Biology class. These students are not ready for a MOOC (and yes, I'm sure about that assessment), and at most, they come in with a "NOVICE" level understanding of the topic. The course is therefore content heavy. None of this so far sets up a good MOOC environment. And the concept of a mechanical MOOC being used is just frightening; this class requires that context be woven with content to build a cognitive framework for higher level biology classes.

So, you have a group of students who require some "instruction", but need more to build their own learning and frameworks. So, taking the concept of blogs, discussions and feeds, build a learning network among members of the class. Open this network to the outside so others who are interested can join in the discussions and activities. Add to this a daily newsletter to keep the conversation going. I took tools from my MOOC experiences, opened the discussion to include new perspectives, and facilitated the discussion. It may be MOOCification, but I think of it more as adapting components that work for my goal.

Now we come to learning objects. Since this is content heavy, and I want outside participation, I have to include learning objects. For a little tangent...

During #MOOCMOOC I came across a common refrain of the MOOC being "organic" and needing no "central" space. I have no idea where this idea came from. All of the "successful" MOOCs I've either participated or lurked on have all had what I refer to as a touchstone, some virtual place where information, objects and artifacts can be found. Perhaps a centralized feed of participant comments, but always with a calendar of activities and some general guidelines. The connections made may be organic, but as we learn from biology, you need to have a scaffold to produce any useful form. So I firmly believe that you need to have some central virtual location.

So, learning objects. For some reason, I feel that this has become a dirty words. What is wrong with a vetted learning object, something which a facilitator/mentor/instructor can use to explain a concept, or even more importantly, start a discussion? Heck, I build learning objects, and yes, I'll open them to everyone (when they're ready).

Enough for now...

While I love the term, I'm not crazy about the underlying concept. It's not that I don't think it can be done, and it is not because I "distrust" MOOCs.

The reason I'm not crazy about the word MOOCify is that it misses out on a critical point: the MOOC is not for all audiences. Instead, I would rather talk about adapting the MOOC model. More specifically, I talk about taking the connectivist foundation of the MOOC, and the tools commonly used in a MOOC, to build a stronger (and more distributed) learning community revolving around a class.

Let me break my thought down using my class as an example.

To start with, the class I'm talking about is a College Level Freshman Biology class. These students are not ready for a MOOC (and yes, I'm sure about that assessment), and at most, they come in with a "NOVICE" level understanding of the topic. The course is therefore content heavy. None of this so far sets up a good MOOC environment. And the concept of a mechanical MOOC being used is just frightening; this class requires that context be woven with content to build a cognitive framework for higher level biology classes.

So, you have a group of students who require some "instruction", but need more to build their own learning and frameworks. So, taking the concept of blogs, discussions and feeds, build a learning network among members of the class. Open this network to the outside so others who are interested can join in the discussions and activities. Add to this a daily newsletter to keep the conversation going. I took tools from my MOOC experiences, opened the discussion to include new perspectives, and facilitated the discussion. It may be MOOCification, but I think of it more as adapting components that work for my goal.

Now we come to learning objects. Since this is content heavy, and I want outside participation, I have to include learning objects. For a little tangent...

During #MOOCMOOC I came across a common refrain of the MOOC being "organic" and needing no "central" space. I have no idea where this idea came from. All of the "successful" MOOCs I've either participated or lurked on have all had what I refer to as a touchstone, some virtual place where information, objects and artifacts can be found. Perhaps a centralized feed of participant comments, but always with a calendar of activities and some general guidelines. The connections made may be organic, but as we learn from biology, you need to have a scaffold to produce any useful form. So I firmly believe that you need to have some central virtual location.

So, learning objects. For some reason, I feel that this has become a dirty words. What is wrong with a vetted learning object, something which a facilitator/mentor/instructor can use to explain a concept, or even more importantly, start a discussion? Heck, I build learning objects, and yes, I'll open them to everyone (when they're ready).

Enough for now...

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Bid a fond farewell to #MOOCMOOC

The the chaotic networking of #MOOCMOOC has come to an end. Final reflections: Like any MOOC, what I took away was inspiration and clarity. Yes, sometimes I also get new skills, learn new tools, or start thinking about things in a radically different way. This one helped to firmly establish my feelings on some things, provided some insights, and gave me some inspiration.

Like any MOOC, I also learned some things from negative examples. The first one is organization. I feel better in a MOOC when there is a touchstone that the community or networks can center around. I don't mean a concept, but some point in virtual space where we can organize things. #change11 was a good example of this. The Canvas LMS system seems like it would be good for some things, but it didn't seem to work for #MOOCMOOC. Part of this could have been the organizing framework, but part is also limitations in the system (I've tried building things in it, but it lacks some functions that I really like for my classes). I think the single biggest problem I had was finding the central platform where all of our comments/blogs/tweets etc... could be collated. Finally found that one Friday...it was under the Dashboard icon which was at the bottom of icon pool. It also wasn't something in Canvas, but an outside link. All that was there were the blog and twitter feeds. I also kept getting random announcements from Canvas, but no central daily newsletter that made sense to me.

Again, I'll go back to #change11. One thing that really helped me there, both when I was actively participating or lurking, was the daily newsletter. It told me what was happening that day, if there was a webinar, but then it had a brief rundown of blogs posted in the last 24 hours. I could use that to go look at what someone said. This time, I really felt like I had to hunt for that information.

The other thing that this showed me was that twitter has a point where there are too many people using one hashtag. There were times I could see people's tweets getting lost, and some were actually interesting points (which I either favored or replied to...I'm bad about retrweeting).

The attempt to use different tools each day to carry out discussions was novel, but sometimes I again felt that connections were missing. For example, Google Docs doesn't work for me when you are there with people you don't know. It works better for me when I can see their comments and have an idea of where they're coming from. I'm sure others had better experiences with that than I, but for me it felt very disconnecting, not connecting. I much rather get into a chat, so I can start feeling out the person's reasons, instead of getting snapshots that don't always relate.

As I said up top, I did leave #MOOCMOOC with some new ideas, fresh inspiration, and some more solid footing. It goes to what I've said about MOOCs here and in tweets, what you get out of a MOOC is what you put into it. Further, no MOOC will match your expectations; each one has surprises and annoyances. We don't all fit the same mold, so not all things will work equally well for everyone.

Like any MOOC, I also learned some things from negative examples. The first one is organization. I feel better in a MOOC when there is a touchstone that the community or networks can center around. I don't mean a concept, but some point in virtual space where we can organize things. #change11 was a good example of this. The Canvas LMS system seems like it would be good for some things, but it didn't seem to work for #MOOCMOOC. Part of this could have been the organizing framework, but part is also limitations in the system (I've tried building things in it, but it lacks some functions that I really like for my classes). I think the single biggest problem I had was finding the central platform where all of our comments/blogs/tweets etc... could be collated. Finally found that one Friday...it was under the Dashboard icon which was at the bottom of icon pool. It also wasn't something in Canvas, but an outside link. All that was there were the blog and twitter feeds. I also kept getting random announcements from Canvas, but no central daily newsletter that made sense to me.

Again, I'll go back to #change11. One thing that really helped me there, both when I was actively participating or lurking, was the daily newsletter. It told me what was happening that day, if there was a webinar, but then it had a brief rundown of blogs posted in the last 24 hours. I could use that to go look at what someone said. This time, I really felt like I had to hunt for that information.

The other thing that this showed me was that twitter has a point where there are too many people using one hashtag. There were times I could see people's tweets getting lost, and some were actually interesting points (which I either favored or replied to...I'm bad about retrweeting).

The attempt to use different tools each day to carry out discussions was novel, but sometimes I again felt that connections were missing. For example, Google Docs doesn't work for me when you are there with people you don't know. It works better for me when I can see their comments and have an idea of where they're coming from. I'm sure others had better experiences with that than I, but for me it felt very disconnecting, not connecting. I much rather get into a chat, so I can start feeling out the person's reasons, instead of getting snapshots that don't always relate.

As I said up top, I did leave #MOOCMOOC with some new ideas, fresh inspiration, and some more solid footing. It goes to what I've said about MOOCs here and in tweets, what you get out of a MOOC is what you put into it. Further, no MOOC will match your expectations; each one has surprises and annoyances. We don't all fit the same mold, so not all things will work equally well for everyone.

Friday, August 17, 2012

How to build a MOOC

This post came from discussions in #MOOCMOOC today. There was a brainstorming session about MOOCs, and a live twitter discussion at #digped. Among the many things that came up was a discussion as to the scale of a MOOC, and an assertion that they had to be MASSIVE. This was followed by a concept that the only way to make a course sustainable was for it to be massive so that it could accumulate revenue. There was also a discussion of how to keep people motivated. So, after a little bit of reflection, I decided to tell a story.

About two years ago, I came to a realization that biology students were not learning biology. What were they learning, no idea. This epiphany came when I was teaching a senior level course. I asked them to define translation, which for biologists is the genetic process where RNA is used by a ribosome to construct a protein; it is the translation of the nucleic acid code into an amino acid code. They couldn't do it. Well, at least not at first. I spent nearly an hour coaxing the definition out of them. They were all upset that I did not just tell them. It may be the first time that I really blew up at a class. For those who are not biologists, this is one component of the CENTRAL DOGMA of biology. Let me say that again, CENTRAL DOGMA. It is something taught in freshman classes, and nearly every course we teach covers it again in more depth. They have come across this term every semester, but none of them could give me a definition of it. One of the students actually said "well if we saw it as an answer choice I could have told you."

This was disheartening, and was a real blow to my desire to teach. I suffered burnout after that semester, and started looking at any alternative I could find (even different careers). It was as bad as my first bout of teacher burnout, which occurred when a student said to me, "you can't fail me, I paid for the class." That is when I came across MOOCs. They were an incredible adventure. It was not about passing a test, but instead, about actively taking part in learning. NOT active learning, but actively taking part in your own learning. BTW...I find most of what is called active learning little different from the instructor playing a game with the students; it rarely makes them an active part of the class. I knew I had to find a way of doing this with my freshman students, but that was the problem. These were not sophisticated learners, they were not actively engaged in their own learning. How to do you get a student to actively become engaged?

My answer was to do certain things in stages, but to make them working on tasks daily a major function of the course. Why? If you are a biologist, then you live with biology every day. The paradigm colors how you perceive the world, as it does with any discipline. Becoming engaged with your discipline is ultimately the only way to master it.

So, I built a structure I originally called a pseudo-(or petite)MOOC. Since then, I've just started calling it Biology Open Learning Opportunities (BOLO). What I did was adapt elements of the MOOC for my audience. I built a structure for their learning, and provided a central virtual place for them to meet (not just the LMS).

The course content was divided into 15 week long topics. Each day, students received a Newsletter that went into depth about an important concept linked to that week's topic. As part of the content, there was a daily challenge for them to blog about. These blogs became the background research for their milestone papers (about 5 weeks worth of material) that were peer reviewed. The three milestone papers became the foundation for their semester end reflective learning paper, which I graded. Along with that, each week had an online quiz that lead to a milestone quiz, which led to an in class final exam (multiple choice, as that is most likely what they will see later). There were other elements as well, but these were two major components of the framework I set up.

Was there resistance? Yes, but by the end, I could actually tell just from the questions being asked and how rapidly my questions were answered, that they were picking up more than any previous semester. It was incredible.

Now, back to what prompted this. An open online course does not have to be massive to use the foundations of a MOOC. A massive class is something that happens, and it does not really work for anyone to try to engineer it. Trying to build a MOOC from the top down, that is, from the administration, does not work. I have yet to see an example of a mandated MOOC that actually worked. MOOCs occur when an instructor opens their class, not when a University VP or Dean decides the school needs one. MOOCs are built by the faculty, and only those that want to go through the effort.

As a continuation of the story, I was invited to an Admin meeting by our Provost (it was a group of us doing "new" things in the classroom). One of Admins said that no one on campus was doing anything with MOOCS. When my turn came, I stood up, turned on the social network I built for my class that was entitled "BIOLOGY MOOC." I looked at the admin and said, "some of us are working with MOOCs."

To Sum Up: the concept of a MOOC can be taken and reworked for your audience. You don't have to keep everything; instead use the tools that best fit your audience. Be courage enough to fail (because something could easily go wrong), but be ready to be surprised by a success. Effective MOOCs can't be built from the top down. It has to come from a faculty member that is ready to open their class. Mandating a MOOC is sure to kill it, because it will not be based on a legitimate learning goal. BTW a legitimate learning goal comes from an instructor that knows their audience.

About two years ago, I came to a realization that biology students were not learning biology. What were they learning, no idea. This epiphany came when I was teaching a senior level course. I asked them to define translation, which for biologists is the genetic process where RNA is used by a ribosome to construct a protein; it is the translation of the nucleic acid code into an amino acid code. They couldn't do it. Well, at least not at first. I spent nearly an hour coaxing the definition out of them. They were all upset that I did not just tell them. It may be the first time that I really blew up at a class. For those who are not biologists, this is one component of the CENTRAL DOGMA of biology. Let me say that again, CENTRAL DOGMA. It is something taught in freshman classes, and nearly every course we teach covers it again in more depth. They have come across this term every semester, but none of them could give me a definition of it. One of the students actually said "well if we saw it as an answer choice I could have told you."

This was disheartening, and was a real blow to my desire to teach. I suffered burnout after that semester, and started looking at any alternative I could find (even different careers). It was as bad as my first bout of teacher burnout, which occurred when a student said to me, "you can't fail me, I paid for the class." That is when I came across MOOCs. They were an incredible adventure. It was not about passing a test, but instead, about actively taking part in learning. NOT active learning, but actively taking part in your own learning. BTW...I find most of what is called active learning little different from the instructor playing a game with the students; it rarely makes them an active part of the class. I knew I had to find a way of doing this with my freshman students, but that was the problem. These were not sophisticated learners, they were not actively engaged in their own learning. How to do you get a student to actively become engaged?

My answer was to do certain things in stages, but to make them working on tasks daily a major function of the course. Why? If you are a biologist, then you live with biology every day. The paradigm colors how you perceive the world, as it does with any discipline. Becoming engaged with your discipline is ultimately the only way to master it.

So, I built a structure I originally called a pseudo-(or petite)MOOC. Since then, I've just started calling it Biology Open Learning Opportunities (BOLO). What I did was adapt elements of the MOOC for my audience. I built a structure for their learning, and provided a central virtual place for them to meet (not just the LMS).

The course content was divided into 15 week long topics. Each day, students received a Newsletter that went into depth about an important concept linked to that week's topic. As part of the content, there was a daily challenge for them to blog about. These blogs became the background research for their milestone papers (about 5 weeks worth of material) that were peer reviewed. The three milestone papers became the foundation for their semester end reflective learning paper, which I graded. Along with that, each week had an online quiz that lead to a milestone quiz, which led to an in class final exam (multiple choice, as that is most likely what they will see later). There were other elements as well, but these were two major components of the framework I set up.

Was there resistance? Yes, but by the end, I could actually tell just from the questions being asked and how rapidly my questions were answered, that they were picking up more than any previous semester. It was incredible.

Now, back to what prompted this. An open online course does not have to be massive to use the foundations of a MOOC. A massive class is something that happens, and it does not really work for anyone to try to engineer it. Trying to build a MOOC from the top down, that is, from the administration, does not work. I have yet to see an example of a mandated MOOC that actually worked. MOOCs occur when an instructor opens their class, not when a University VP or Dean decides the school needs one. MOOCs are built by the faculty, and only those that want to go through the effort.

As a continuation of the story, I was invited to an Admin meeting by our Provost (it was a group of us doing "new" things in the classroom). One of Admins said that no one on campus was doing anything with MOOCS. When my turn came, I stood up, turned on the social network I built for my class that was entitled "BIOLOGY MOOC." I looked at the admin and said, "some of us are working with MOOCs."

To Sum Up: the concept of a MOOC can be taken and reworked for your audience. You don't have to keep everything; instead use the tools that best fit your audience. Be courage enough to fail (because something could easily go wrong), but be ready to be surprised by a success. Effective MOOCs can't be built from the top down. It has to come from a faculty member that is ready to open their class. Mandating a MOOC is sure to kill it, because it will not be based on a legitimate learning goal. BTW a legitimate learning goal comes from an instructor that knows their audience.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

Plagiarism (Why I MOOC)

Yesterday I was mired in a project, so I didn't join in the #MOOCMOOC discussions. Today, the facilitators have assigned everyone to work with Storify. I'm only a marginal fan of Storify, as I haven't really gotten good submissions from students (they are overwhelmed in most of life that this was just a little too overwhelming). In general I see it as an alternative route for people it speaks to. Since I'm not really in that group, I'm going to hold off on this leg of the tech tour that is #MOOCMOOC.

Ultimately, the reason why I MOOC is to listen to what other people are thinking and talking about, and then reflect on that. It is the alternative perspectives, the conflicting views, and the stray thought that leads to a revelation. The facilitators at #MOOCMOOC have not really added to the conversation (articles and tools have been out there for a while), but what they have done is provide a time point where people interested in open learning connect. That is ultimately the story that I want to take part in this week.

Today in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Jeffery R. Young presented an article entitled Dozens of Plagiarism Incidents Are Reported in Coursera's Free Online Courses. The interesting item from the article is that people will plagiarize in an online course even when it is for no credit! The author further discusses how some view this as a teachable moment (some cultures see copying as a way of showing honor and esteem for the work's creator), cautioning people from being over zealous or flaming the offender.

The part I loved the best was when a student claimed that they did not know that copying was wrong. I had a student tell me that recently (a senior). I asked him if he had read my syllabus (which discusses academic honesty), or the section on plagiarism on every assignment, or the tutorial that was posted on plagiarism. He avoided the questions, saying that he did not know copying was wrong. This conversation kept going on and on until he finally admitted that he did not read the syllabus or take the tutorial, and only glanced at the assignment instructions. The teachable moment here was a little more basic (read what you are assigned to read, and read instructions).

I try to make plagiarism very simple for my students. We are in the biological sciences, and it is extremely rare for anyone to use quotes in scientific papers. So the first thing I tell students is that they may not quote or copy from any source. The next thing I emphasize is that they must use their own words. That one phrase, their own words, is repeated throughout the semester. If they come and ask, I tell them that I'll sit down and help them; I never give them the sentence, but try to help them work out what they want to say. But, this is where the reflection begins...

Today, I started really asking myself what I consider plagiarism in the world of web 2.0. When is it sharing, remixing or plagiarism? There are posts in facebook, and even twitter, that I know were taken directly off of a website with no citation or hyperlink (which I'm starting to see as a form of citation). Would I consider that plagiarism? No, not really. But why?

We have the distinction between formal and informal writing. A facebook post is considered informal, as is twitter and any other form of social media. In the informal setting, we don't use all the formal rules of English. It is in this social setting that we can hash out our thoughts, put them out there for people to comment on, critic, or just to return to for reflection.

Back in high school, when I had to write a term paper, I had to sit there and make note cards that would be turned in for a grade. There was a formal structure for making these note cards, and a formal structure for organizing them so that they could be linked to my formal outline. All of the instructions were codified in my textbook and had been presented to me in lecture by my teacher. We all had to follow that structure. As you may be able to tell, my mind did not work in that formal structure. I bowed under the academic pressure and did it, then threw them out before I started to write the paper. It actually amazes me when I see colleagues using that system; my mind just does not wrap around that structure. (Actually, let me just say that HATED writing high school term papers, mainly because they were so fragging structured).

The reason for that story is to reconsider how people can use informal settings to work out thoughts. On those pesky note cards, you were suppose to copy "QUOTES" from the book, as well as make notes. Well, can't those also be done in some form of digital setting (and no I don't want digital note cards). What if you could allow others to comment? In other words, what if informal writing assignments are used as a way to help students hash out their thoughts.

I didn't realize it at first, but this I think was the reasoning behind the blogging leading to milestone papers I do in my classes. The idea is simple, and now I'm seeing it as more powerful. The blog is a tool, open to others in the class or world, where you work out a specific concept. You then bring the blogs together in constructing your paper. The paper is FORMAL, thus it must follow the formal rules of English, be cited, and free of plagiarism. The blog was where you took the work of others and converted it into your own words.

I'll leave this for now, but I would love to hear your thoughts on this idea...

Ultimately, the reason why I MOOC is to listen to what other people are thinking and talking about, and then reflect on that. It is the alternative perspectives, the conflicting views, and the stray thought that leads to a revelation. The facilitators at #MOOCMOOC have not really added to the conversation (articles and tools have been out there for a while), but what they have done is provide a time point where people interested in open learning connect. That is ultimately the story that I want to take part in this week.

Today in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Jeffery R. Young presented an article entitled Dozens of Plagiarism Incidents Are Reported in Coursera's Free Online Courses. The interesting item from the article is that people will plagiarize in an online course even when it is for no credit! The author further discusses how some view this as a teachable moment (some cultures see copying as a way of showing honor and esteem for the work's creator), cautioning people from being over zealous or flaming the offender.

The part I loved the best was when a student claimed that they did not know that copying was wrong. I had a student tell me that recently (a senior). I asked him if he had read my syllabus (which discusses academic honesty), or the section on plagiarism on every assignment, or the tutorial that was posted on plagiarism. He avoided the questions, saying that he did not know copying was wrong. This conversation kept going on and on until he finally admitted that he did not read the syllabus or take the tutorial, and only glanced at the assignment instructions. The teachable moment here was a little more basic (read what you are assigned to read, and read instructions).

I try to make plagiarism very simple for my students. We are in the biological sciences, and it is extremely rare for anyone to use quotes in scientific papers. So the first thing I tell students is that they may not quote or copy from any source. The next thing I emphasize is that they must use their own words. That one phrase, their own words, is repeated throughout the semester. If they come and ask, I tell them that I'll sit down and help them; I never give them the sentence, but try to help them work out what they want to say. But, this is where the reflection begins...

Today, I started really asking myself what I consider plagiarism in the world of web 2.0. When is it sharing, remixing or plagiarism? There are posts in facebook, and even twitter, that I know were taken directly off of a website with no citation or hyperlink (which I'm starting to see as a form of citation). Would I consider that plagiarism? No, not really. But why?

We have the distinction between formal and informal writing. A facebook post is considered informal, as is twitter and any other form of social media. In the informal setting, we don't use all the formal rules of English. It is in this social setting that we can hash out our thoughts, put them out there for people to comment on, critic, or just to return to for reflection.

Back in high school, when I had to write a term paper, I had to sit there and make note cards that would be turned in for a grade. There was a formal structure for making these note cards, and a formal structure for organizing them so that they could be linked to my formal outline. All of the instructions were codified in my textbook and had been presented to me in lecture by my teacher. We all had to follow that structure. As you may be able to tell, my mind did not work in that formal structure. I bowed under the academic pressure and did it, then threw them out before I started to write the paper. It actually amazes me when I see colleagues using that system; my mind just does not wrap around that structure. (Actually, let me just say that HATED writing high school term papers, mainly because they were so fragging structured).

The reason for that story is to reconsider how people can use informal settings to work out thoughts. On those pesky note cards, you were suppose to copy "QUOTES" from the book, as well as make notes. Well, can't those also be done in some form of digital setting (and no I don't want digital note cards). What if you could allow others to comment? In other words, what if informal writing assignments are used as a way to help students hash out their thoughts.

I didn't realize it at first, but this I think was the reasoning behind the blogging leading to milestone papers I do in my classes. The idea is simple, and now I'm seeing it as more powerful. The blog is a tool, open to others in the class or world, where you work out a specific concept. You then bring the blogs together in constructing your paper. The paper is FORMAL, thus it must follow the formal rules of English, be cited, and free of plagiarism. The blog was where you took the work of others and converted it into your own words.

I'll leave this for now, but I would love to hear your thoughts on this idea...

Reflecting on "what is learning?"

On Tuesday, George Siemens posted a #MOOCMOOC Video about his thoughts on learning and our attempts to structure learning environments. One of the first things he brought up is that you "can't model the behavior of others." This got me thinking as I worked to clean up some projects yesterday.

As often occurs, the thoughts are various and self-contradicting at times. So what I was going to do is write about some of these thoughts to see what other people might think.

First: Lectures...why do we hold onto them.

Last week, I was in a 'hybrid education' workshop here at Georgia State University. One of the participants said that they did not feel comfortable giving up lecture. I've heard this before, and last week, as before, the answer came out that how else do you know if they got the content if you don't lecture? I think one reason that some instructors hold onto lecture is a perception of "doing your job". Your suppose to instruct students, therefore you must show that you have instructed, and what better way to do this than to lecture. Some people also consider themselves good lecturers. They make it fun, they tell jokes, tell stories, dance around in costumes, or whatever to help motivate engagement of students. For many though, I think it comes down simply to the idea that as long as I have presented to the students the content, my job is done. Then all they have to do is assess to see if the student got the knowledge they imparted.

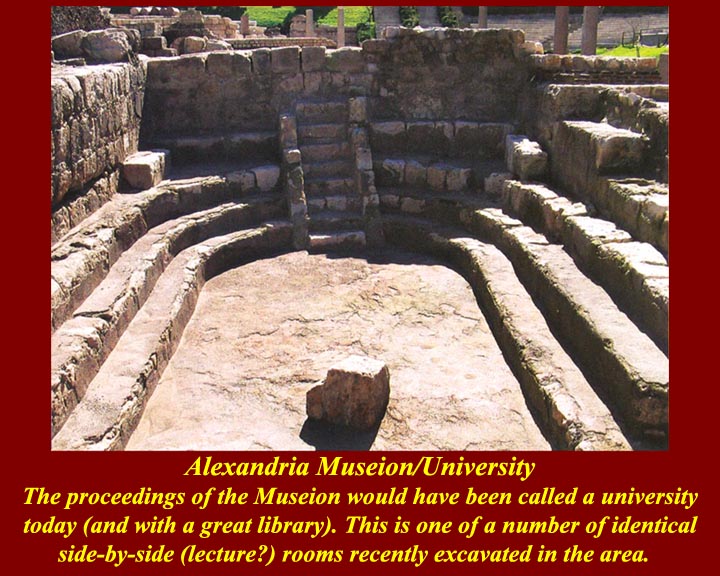

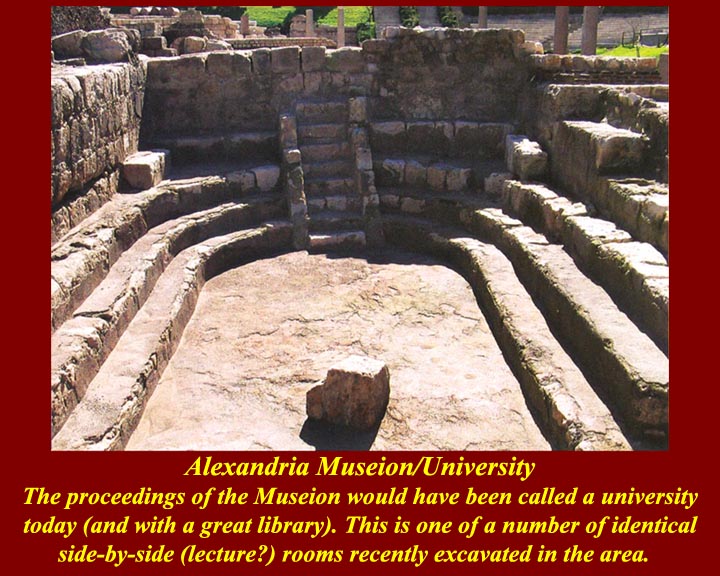

I don't think we hold on to lectures because it is the best model of education, but because we have a long history of using this style to convey knowledge. Archaeologists are now showing us that this educational style may be older than we thought.

To sum this up: many people hold on to lecture styles because they think it is the only way to prove that they presented the information to students.

Second: Modeling behavior. George mentioned that modeling behavior, especially in learning, is "impossible". Still, we have done it for generations. When all we had were experts that could present knowledge in person (no on-demand access to information), the lecture model seemed to work. We also model social behavior from a young age, and generally teach children what society holds to be good ethical/moral behavior. Does it always work? NO. But for the vast majority of us, it worked in part. When you look at children (up to around age 6), you have to have some structure, some idea about their developmental needs. As they grow older, their needs change.

So the question that keeps coming to mind is when and how do you start adapting to the changing developmental needs of the individual. As I've mentioned before, most freshmen are not ready for a fully open class like the cMOOCs. They are not intellectually inferior, but developmentally, they are not fully mature. In situational leadership concepts, they are still in maturity stage 1: they lack the self-reflection (which comes with maturity) and self-direction (they don't know what they need to learn), as well as lacking the ability (or unwilling) to accept the responsibility of this learning model. As such, they still require direction (structure) to learn the self-reflection and self-direction needed, as well as to gain confidence to accept the responsibility of their own education. The question now becomes how to model something like this. My answer is that you have to provide multiple avenues, and low stakes assignments.

One thing to note: as we move further into the digital age, it is very possible (even likely) that students will change in what they need from different educational levels. I'm not suggesting that the average 12 year old will be ready for college, but instead that what we need to build to assist their education will be different.

That's all for now. Back to projects.

As often occurs, the thoughts are various and self-contradicting at times. So what I was going to do is write about some of these thoughts to see what other people might think.

First: Lectures...why do we hold onto them.

Last week, I was in a 'hybrid education' workshop here at Georgia State University. One of the participants said that they did not feel comfortable giving up lecture. I've heard this before, and last week, as before, the answer came out that how else do you know if they got the content if you don't lecture? I think one reason that some instructors hold onto lecture is a perception of "doing your job". Your suppose to instruct students, therefore you must show that you have instructed, and what better way to do this than to lecture. Some people also consider themselves good lecturers. They make it fun, they tell jokes, tell stories, dance around in costumes, or whatever to help motivate engagement of students. For many though, I think it comes down simply to the idea that as long as I have presented to the students the content, my job is done. Then all they have to do is assess to see if the student got the knowledge they imparted.

I don't think we hold on to lectures because it is the best model of education, but because we have a long history of using this style to convey knowledge. Archaeologists are now showing us that this educational style may be older than we thought.

To sum this up: many people hold on to lecture styles because they think it is the only way to prove that they presented the information to students.

Second: Modeling behavior. George mentioned that modeling behavior, especially in learning, is "impossible". Still, we have done it for generations. When all we had were experts that could present knowledge in person (no on-demand access to information), the lecture model seemed to work. We also model social behavior from a young age, and generally teach children what society holds to be good ethical/moral behavior. Does it always work? NO. But for the vast majority of us, it worked in part. When you look at children (up to around age 6), you have to have some structure, some idea about their developmental needs. As they grow older, their needs change.

So the question that keeps coming to mind is when and how do you start adapting to the changing developmental needs of the individual. As I've mentioned before, most freshmen are not ready for a fully open class like the cMOOCs. They are not intellectually inferior, but developmentally, they are not fully mature. In situational leadership concepts, they are still in maturity stage 1: they lack the self-reflection (which comes with maturity) and self-direction (they don't know what they need to learn), as well as lacking the ability (or unwilling) to accept the responsibility of this learning model. As such, they still require direction (structure) to learn the self-reflection and self-direction needed, as well as to gain confidence to accept the responsibility of their own education. The question now becomes how to model something like this. My answer is that you have to provide multiple avenues, and low stakes assignments.

One thing to note: as we move further into the digital age, it is very possible (even likely) that students will change in what they need from different educational levels. I'm not suggesting that the average 12 year old will be ready for college, but instead that what we need to build to assist their education will be different.

That's all for now. Back to projects.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Perceived Problems in MOOCs (Part 4: A Degree Means Something)

I'm skipping the fourth proposition in David Youngberg's April 13th Chronicle commentary because it is very ill conceived and insulting to those who have degrees in English and the other 'Liberal Arts'. Not only does it show a poor definition of liberal arts, but it also shows a poor model of assessment. Instead, I'm going to focus on the fifth poposition.

David Youngberg's fifth fundamental problem with a MOOC is that "Money can substitute for ability." It took me a couple times reading through this part of the article to figure out what he was trying to get at with this title. So that my comments are clear, I've pasted his paragraph dealing with this proposition. I've also highlighted some points I feel are critical.

Higher education leads to a better salary because a college degree is a signal. Yes, you gain practical skills in college, but a degree is largely about showing potential employers that you're smart and hard working. Grades function the same way. Get an A in philosophy and people will find you impressive even if what you learned isn't practical. But the signal only works if most people didn't get an A. Signaling is relative.

If your wondering, the highlight colors are akin to National Security warnings. In this case, they are warnings about a really bad perceptual model: that getting a degree at a prestigious school is more important than learning anything, i.e., that money buys success. Thoughout this whole part of the article, you start to see through the mask. A degree should be reserved for the elite. Beyond that, there are some major misconceptions that my friends in industry would really gripe at.

Let's start with "...a college degree is a signal." That is very true. It is a signal, but of what? Does a college degree really show that a person is "smart and hardworking"? NO, and many people that I meet are starting to realize that, both in academics and in industry. What is more important is the concept of competencies. You want to know what the person is competent at doing. The Bolonga process is based on showing competencies, as is the Degree Qualificaiton Profile from the Lumina Foundation here in the states. How many corporate giants have to say that they are looking for competent people before the message is heard? David Youngberg focuses his attention on getting an A as the standard of excellence, but what does an A tell you? Is the person smart, or could they game the system? A colleague shared this video with me during #moocmocc.

Tom Peters is a strong voice in business management, and he is telling people that the A does not demonstrate a person who going to be good for the company. But why? Learning how to game an academic situation to get an A does not provide the skills needed (or desired) in a rapidly evolving global economy/society. Do you really want a passive learner who only knows how pass an exam, but not necessarily learn and create, manning your operations?

David Youngberg is more concerned with impressing people with a good grade, instead of impressing them with skills, abilities, knowledge or even a variety of intellectual models. Philosophy for him is not practical, though it has informed even his discipline for centuries. The liberal arts are downplayed to business communication, instead of being the seeds for inspiration and innovation. How many of our greatest thinkers were also accomplished artists or musicians? (here is a good article if your interested: http://www.creativitypost.com/create/how_geniuses_think/).

"Signals are relative," and that is very true. But what are the signals we are now looking at, and what do they tell us?

After this last problem, David Youngberg descends into a strange account of why you don't want to make education cheap. This seems inspired by game theory, but is ultimately reductio ad absurdum, with the conclusion that if education was cheap, everyone would get an A, and thus devalue the meaning of an A. I think he is holding a little to strongly to the supremecy of an A.

For me, the article revealed a very odd way of looking at the world and education, and the arguments presented were not well considered and out of touch with how the world is changing.

Does this mean that I view online education and MOOCs as the saviors of education? Do I think that Udacity will ultimately doom universities and college? NO.

What is occuring now in online education is equivalent to children playing in a sandbox. We have new toys, and we're learning to use them to influence our world. Will all of our play produce something that works successfully? NO, but it will change how we play our games.

As we move into this new age, we are going to what to know the competencies of an individual, not just some grade given. This does not mean just some sort of certificate or badge. We are going to want to see what the person is capable of doing (the growing use of ePortfolios is a great example). The MOOC as it stands now may not even be around in 10 years save for a historic construct. Individuals will take this foundation and adapt, remix, and rebuild, but that is the nature of Web 2.0 and the amazing connections that we can now form in an information rich era. David Youngberg's arguments are just a dying gasp from a comatose educational era.

David Youngberg's fifth fundamental problem with a MOOC is that "Money can substitute for ability." It took me a couple times reading through this part of the article to figure out what he was trying to get at with this title. So that my comments are clear, I've pasted his paragraph dealing with this proposition. I've also highlighted some points I feel are critical.

Higher education leads to a better salary because a college degree is a signal. Yes, you gain practical skills in college, but a degree is largely about showing potential employers that you're smart and hard working. Grades function the same way. Get an A in philosophy and people will find you impressive even if what you learned isn't practical. But the signal only works if most people didn't get an A. Signaling is relative.

If your wondering, the highlight colors are akin to National Security warnings. In this case, they are warnings about a really bad perceptual model: that getting a degree at a prestigious school is more important than learning anything, i.e., that money buys success. Thoughout this whole part of the article, you start to see through the mask. A degree should be reserved for the elite. Beyond that, there are some major misconceptions that my friends in industry would really gripe at.

Let's start with "...a college degree is a signal." That is very true. It is a signal, but of what? Does a college degree really show that a person is "smart and hardworking"? NO, and many people that I meet are starting to realize that, both in academics and in industry. What is more important is the concept of competencies. You want to know what the person is competent at doing. The Bolonga process is based on showing competencies, as is the Degree Qualificaiton Profile from the Lumina Foundation here in the states. How many corporate giants have to say that they are looking for competent people before the message is heard? David Youngberg focuses his attention on getting an A as the standard of excellence, but what does an A tell you? Is the person smart, or could they game the system? A colleague shared this video with me during #moocmocc.

Tom Peters is a strong voice in business management, and he is telling people that the A does not demonstrate a person who going to be good for the company. But why? Learning how to game an academic situation to get an A does not provide the skills needed (or desired) in a rapidly evolving global economy/society. Do you really want a passive learner who only knows how pass an exam, but not necessarily learn and create, manning your operations?

David Youngberg is more concerned with impressing people with a good grade, instead of impressing them with skills, abilities, knowledge or even a variety of intellectual models. Philosophy for him is not practical, though it has informed even his discipline for centuries. The liberal arts are downplayed to business communication, instead of being the seeds for inspiration and innovation. How many of our greatest thinkers were also accomplished artists or musicians? (here is a good article if your interested: http://www.creativitypost.com/create/how_geniuses_think/).

"Signals are relative," and that is very true. But what are the signals we are now looking at, and what do they tell us?

After this last problem, David Youngberg descends into a strange account of why you don't want to make education cheap. This seems inspired by game theory, but is ultimately reductio ad absurdum, with the conclusion that if education was cheap, everyone would get an A, and thus devalue the meaning of an A. I think he is holding a little to strongly to the supremecy of an A.

For me, the article revealed a very odd way of looking at the world and education, and the arguments presented were not well considered and out of touch with how the world is changing.

Does this mean that I view online education and MOOCs as the saviors of education? Do I think that Udacity will ultimately doom universities and college? NO.

What is occuring now in online education is equivalent to children playing in a sandbox. We have new toys, and we're learning to use them to influence our world. Will all of our play produce something that works successfully? NO, but it will change how we play our games.

As we move into this new age, we are going to what to know the competencies of an individual, not just some grade given. This does not mean just some sort of certificate or badge. We are going to want to see what the person is capable of doing (the growing use of ePortfolios is a great example). The MOOC as it stands now may not even be around in 10 years save for a historic construct. Individuals will take this foundation and adapt, remix, and rebuild, but that is the nature of Web 2.0 and the amazing connections that we can now form in an information rich era. David Youngberg's arguments are just a dying gasp from a comatose educational era.

Perceived Problems in MOOC (Part 3 -weird employees)

NOTE: yes, I'm blogging multiple times today. The April 13th chronicle commentary by David Youngberg really inspired me to put down some thoughts regarding MOOCs. So there will be a couple more posts today.

Daivd Youngberg's third criticism of MOOCs (and I would gather all online degrees) is that "employers avoid weird people." While repetitive from my last blog, but...WHAT? I'm not sure what business he is talking about, but I know some mighty strange people who work in all manner or technical fields. Come down to DragonCon here in Atlanta, GA, and I'll introduce you to some of them (even those who have high ranking positions). In this case, we may need to have a definition about weird if we are going to accept this proposition.

What bothers me about this argument is that Youngberg is either tell those of us who participate in MOOCs that we are weird, or that companies are so stupid that they can't spot a potential problem applicant. How many time have you had students who thought they were going to change the world? How many of you have had young assistants or graduate students who thought they were going to lead the next revolution in your discipline? It is plain old neurophysiology and aging at work. They all soon realize that they are not as revolutionary as they thought, and the work environment molds them.

Most HR professionals I know can spot the non-team player fast, and coming from a college or university does not guarantee that a person will be a team player. I don't see where the link between "unconventional degree" and "radical thinker" comes from. There is no reference to studies, no evidence, so I left to wonder where this idea started.

Of all the arguments, this is the one that seems the most absurd and out of touch. Most of the people I know in HR and corporations are looking for people who are competent and don't need extensive training. They have a probation period to feel out how they will fit in. I don't see an unconventional degree as labelling them weird, and let's face it, even the best screening practices fail.

Daivd Youngberg's third criticism of MOOCs (and I would gather all online degrees) is that "employers avoid weird people." While repetitive from my last blog, but...WHAT? I'm not sure what business he is talking about, but I know some mighty strange people who work in all manner or technical fields. Come down to DragonCon here in Atlanta, GA, and I'll introduce you to some of them (even those who have high ranking positions). In this case, we may need to have a definition about weird if we are going to accept this proposition.

What bothers me about this argument is that Youngberg is either tell those of us who participate in MOOCs that we are weird, or that companies are so stupid that they can't spot a potential problem applicant. How many time have you had students who thought they were going to change the world? How many of you have had young assistants or graduate students who thought they were going to lead the next revolution in your discipline? It is plain old neurophysiology and aging at work. They all soon realize that they are not as revolutionary as they thought, and the work environment molds them.

Most HR professionals I know can spot the non-team player fast, and coming from a college or university does not guarantee that a person will be a team player. I don't see where the link between "unconventional degree" and "radical thinker" comes from. There is no reference to studies, no evidence, so I left to wonder where this idea started.

Of all the arguments, this is the one that seems the most absurd and out of touch. Most of the people I know in HR and corporations are looking for people who are competent and don't need extensive training. They have a probation period to feel out how they will fit in. I don't see an unconventional degree as labelling them weird, and let's face it, even the best screening practices fail.

Perceived Problems in MOOC (Part 2: Star Students)

Continuing my thoughts on the perceived problems in MOOCs as presented by David Youngberg's April 13, 2012 commentary in the Chronicle, I come to the second perceived problem: that the "star student can't shine." WHAT?

What is a star student? Is it the one that get's the A because they know how to take multiple choice tests? Is it the student that has learned to cram and flush so effectively that in one night they can game the course content to get a good exam grade? Is the student kisses up by always coming by your office to ask you a minor question (and really never gets around to asking about anything useful)? Or is it the arch manipulator? These are all negative stereotypes, but I've seen colleagues holding these people up as star students. Once their in a challenging class (such as a course taught through case studies), they flounder and complain.

Both in online and face-to-face, I can spot the students that are trying. I can spot the students that are giving it their all, even if they struggle through the whole course. I've had students that I've said are some of the brightest and best, but they still only got a B out of my class. Why? Because they were great students. They learned. Even after years, they still remembered what they learned in my class. They can still point to AHA moments (now in the dictionary) where they either learned something about the content or about themselves. In my class they may not have been an A student, but they were a star student. They were higher achieving than those that got the A.

The question is not can star students shine, but what do you consider a star student? Ask yourself, have I given possibilities for students to shine? How do I acknowledge a student's achievement? The idea that a person can not shine in different media is ludicrous. It makes me wonder if David Youngberg felt under appreciated in the Udacity course, and what he considers a star student.

About being under appreciated, we all feel that way at some point or another, but do you participate in a MOOC or online course to feel appreciated? When I participate in something like a MOOC like #MOOCMOOC going on right now, I'm doing it to learn something, gain inspiration or build connections (networks). What is strange, those students who shine for me, are the ones who are trying to learn the material in the course, those who struggle with concepts, ask good questions, and sit in my office near to tears because they don't understand something. In short, those that are taking the challenge of the learning opportunities.

What is a star student? Is it the one that get's the A because they know how to take multiple choice tests? Is it the student that has learned to cram and flush so effectively that in one night they can game the course content to get a good exam grade? Is the student kisses up by always coming by your office to ask you a minor question (and really never gets around to asking about anything useful)? Or is it the arch manipulator? These are all negative stereotypes, but I've seen colleagues holding these people up as star students. Once their in a challenging class (such as a course taught through case studies), they flounder and complain.

Both in online and face-to-face, I can spot the students that are trying. I can spot the students that are giving it their all, even if they struggle through the whole course. I've had students that I've said are some of the brightest and best, but they still only got a B out of my class. Why? Because they were great students. They learned. Even after years, they still remembered what they learned in my class. They can still point to AHA moments (now in the dictionary) where they either learned something about the content or about themselves. In my class they may not have been an A student, but they were a star student. They were higher achieving than those that got the A.

The question is not can star students shine, but what do you consider a star student? Ask yourself, have I given possibilities for students to shine? How do I acknowledge a student's achievement? The idea that a person can not shine in different media is ludicrous. It makes me wonder if David Youngberg felt under appreciated in the Udacity course, and what he considers a star student.

About being under appreciated, we all feel that way at some point or another, but do you participate in a MOOC or online course to feel appreciated? When I participate in something like a MOOC like #MOOCMOOC going on right now, I'm doing it to learn something, gain inspiration or build connections (networks). What is strange, those students who shine for me, are the ones who are trying to learn the material in the course, those who struggle with concepts, ask good questions, and sit in my office near to tears because they don't understand something. In short, those that are taking the challenge of the learning opportunities.

Perceived Problems in MOOCs - (part 1: cheating)

In the chronicle yesterday, David Youngberg wrote a commentary titled 'Why Online Education Won't Replace College - Yet'. While he makes one good point, there are many other problems I have with his position. Some are just different ways of thinking about education and assessment, while others are perspective.

Youngberg's first criticism is in cheating, namely that if a MOOC (his central concern in online education) were for credit, cheating would be rampant. Well, cheating is already rampant in higher education, and it is sometimes very difficult to catch. My favorite was the student who took pictures of the test, sent them to other students waiting outside, who then came in "late" for the exam (the first person showed up early). Yes, they got caught.

For me the issue of cheating revolves around the goal of the assignment. Youngberg does point out that in the Udacity course he enrolled in did allow collaboration on discussions, but then goes on with the idea that there would be cheating if the course was for credit. I state again, your concept of cheating is ultimately tied up in what you view as the GOAL of the assignment.

In my classes, I use a number of online quizzes as formative assessments. Students have unlimited attempts, and the database of questions that randomize between each quiz is large. I encourage the students to cooperate in answering the questions. The goal is to get them thinking, to reference their textbooks, and online sources. I want them to work on finding the answers. Colleagues have accused me of allowing students to cheat, because a quiz "should reflect what the student knows." How do you argue with someone whose perception of assessment is so myopic? Even online exams (which are not worth a killer amount of points) are not proctored. Could the students be sitting next to each other? Could they be comparing? Could they be looking thing up? Yes, and I expect that they are doing that, but they are still learning.

Let me state again, these are not punitive exams point wise. These exams are not worth 1/3rd of their grade, like most people post exams. If they do poorly, it doesn't stop them. Instead, it shows them where their still struggling.

This past semester, my students only had one in class exam: the final. Even then, they had a second chance to take it if they did poorly (new question set though). I had fewer suspicious students during that final exam than I've ever had before. Fewer students with stray glances, furtive looks at what could be a crib sheet, or even the tell-tale bulge of a cellphone. I took the pressure off the exams, and the cheating went down.

When I asked students how much help they got when taking the exams, they said a little. When I asked them to explain, they said they sat near someone, but that the other person wasn't that helpful (they had 50 minutes to do a 50 question multiple choice). Some admitted that they looked up an answer they couldn't figure out. Strangely, it didn't both me. I still saw it as learning. That, and I ended out with the highest average on the final exam (first round) than I've ever had.

So, to sum up, I think cheating is predicated on the goals you have for your assessments.

Youngberg's first criticism is in cheating, namely that if a MOOC (his central concern in online education) were for credit, cheating would be rampant. Well, cheating is already rampant in higher education, and it is sometimes very difficult to catch. My favorite was the student who took pictures of the test, sent them to other students waiting outside, who then came in "late" for the exam (the first person showed up early). Yes, they got caught.

For me the issue of cheating revolves around the goal of the assignment. Youngberg does point out that in the Udacity course he enrolled in did allow collaboration on discussions, but then goes on with the idea that there would be cheating if the course was for credit. I state again, your concept of cheating is ultimately tied up in what you view as the GOAL of the assignment.

In my classes, I use a number of online quizzes as formative assessments. Students have unlimited attempts, and the database of questions that randomize between each quiz is large. I encourage the students to cooperate in answering the questions. The goal is to get them thinking, to reference their textbooks, and online sources. I want them to work on finding the answers. Colleagues have accused me of allowing students to cheat, because a quiz "should reflect what the student knows." How do you argue with someone whose perception of assessment is so myopic? Even online exams (which are not worth a killer amount of points) are not proctored. Could the students be sitting next to each other? Could they be comparing? Could they be looking thing up? Yes, and I expect that they are doing that, but they are still learning.

Let me state again, these are not punitive exams point wise. These exams are not worth 1/3rd of their grade, like most people post exams. If they do poorly, it doesn't stop them. Instead, it shows them where their still struggling.

This past semester, my students only had one in class exam: the final. Even then, they had a second chance to take it if they did poorly (new question set though). I had fewer suspicious students during that final exam than I've ever had before. Fewer students with stray glances, furtive looks at what could be a crib sheet, or even the tell-tale bulge of a cellphone. I took the pressure off the exams, and the cheating went down.

When I asked students how much help they got when taking the exams, they said a little. When I asked them to explain, they said they sat near someone, but that the other person wasn't that helpful (they had 50 minutes to do a 50 question multiple choice). Some admitted that they looked up an answer they couldn't figure out. Strangely, it didn't both me. I still saw it as learning. That, and I ended out with the highest average on the final exam (first round) than I've ever had.

So, to sum up, I think cheating is predicated on the goals you have for your assessments.

Monday, August 13, 2012

Good MOOC/Bad MOOC

When I hear the Good/Bad discussion, this is the image that comes to mind. Have gone through a number of MOOCs over the past two years, both as lurker and active participant, there are some likes and dislikes I can identify.

1. I like to have conversations with other participants. If the MOOC facilitators start talking at me, then I'm not likely to stay. When I sign up for a MOOC, I'm not neccessarily looking for a "class" in discipline X. What I'm generally looking for is connection to an ever widening community of people interested in new models of learning. Since I have a tendency to become a hermit when I focus on a problem, MOOCs and other discussion help provide a touchstone and a group willing to bounce around ideas (or even tell me when I'm going the wrong direction).

Being part of a MOOC where the facilitator gets in the way...well that becomes a problem. Example: When the facilitator becomes the dominant voice of the MOOC.

2. A central repository of objects, such as blogs, that can be reviewed and reflected upon. This requires some web framework or system, but provides the participant a place to go to just reflect on what is going on across the MOOC. If I have to go to four different sites just to keep up with the main thought lines of the MOOC, then I'm going to go to take what I can and my own way.

As a clarification: we all make our own paths through a MOOC, and that is one of the strengths of a MOOC. If the framework though does not support building that path, and instead it is just a jumble of various tools being used, then you're looking at building your path through a briar patch (most likely getting stuck or lost).

One very important element I've found in what I call good MOOCs is that there is a repository where I can go and scan through things looking for posts/tweets/discussion that inspire me. I can find and follow central threads, or what I've come to call the thought lines of the MOOC. Fishing for tought lines is a pain, as is trying to tease them out of multiple disconnected tools. (The take home message: you need connected tools).

3. Time: Change 11 was one of my favorite MOOCs, but it went on for a long time. My life changed, the semester changes, and I started a number of projects. As a result, I went into lurker mode in the MOOC. While I can see why people may like a long duration MOOC, I myself like MOOCs that are about two-three months in length. It gives you time to get your feet wet and really get involved. It also provides more opportunities to actually build networks.

While I like what I've seen and gotten from #MOOCMOOC, I have to say it feels like a speed dating session. I can barely remember what I commented on today. There are advantages to this (you see and do very quickly, and there is very little chance of burning out as the weeks drag on), but there are disadvantages (namely going so fast you're not sure what you've done).

4. Newsletters: Having daily contact with the MOOC is essential and inspiring. Having something in my email box to remind me about a topic, or better yet, showing me some important threads, is amazingly helpful. Getting an admin note with no content, not so inspiring. With that said, having 10+ messages every day (or every hour in one case) is not so great (I really had to change my notifications on that one). With no newsletters, I feel a little left on my own. With 10+ coming from the facilitator, I feel harassed.

One thing that needs to be emphasized, is that the newsletters are most helpful when it has content or links that help you bring the previous day/week content into focus.

____________________________________________________________________________

If you've read my previous posts, you may have seen that I feel that everyone can adapt the foundations of MOOCs to their own situations and audience. Most of my courses are for undergraduates, and as such, they are not ready for what is seen by many as a MOOC (they are not ready to self-organize). My comments here are a reflection of what I like when I join a MOOC. What I do in my classes is different because my audience is different. If I were to do an open course dealing with an audience use to self-actualized learning (what we're doing in #MOOCMOOC), then my interactions and framework would be different.

1. I like to have conversations with other participants. If the MOOC facilitators start talking at me, then I'm not likely to stay. When I sign up for a MOOC, I'm not neccessarily looking for a "class" in discipline X. What I'm generally looking for is connection to an ever widening community of people interested in new models of learning. Since I have a tendency to become a hermit when I focus on a problem, MOOCs and other discussion help provide a touchstone and a group willing to bounce around ideas (or even tell me when I'm going the wrong direction).

Being part of a MOOC where the facilitator gets in the way...well that becomes a problem. Example: When the facilitator becomes the dominant voice of the MOOC.

2. A central repository of objects, such as blogs, that can be reviewed and reflected upon. This requires some web framework or system, but provides the participant a place to go to just reflect on what is going on across the MOOC. If I have to go to four different sites just to keep up with the main thought lines of the MOOC, then I'm going to go to take what I can and my own way.

As a clarification: we all make our own paths through a MOOC, and that is one of the strengths of a MOOC. If the framework though does not support building that path, and instead it is just a jumble of various tools being used, then you're looking at building your path through a briar patch (most likely getting stuck or lost).

One very important element I've found in what I call good MOOCs is that there is a repository where I can go and scan through things looking for posts/tweets/discussion that inspire me. I can find and follow central threads, or what I've come to call the thought lines of the MOOC. Fishing for tought lines is a pain, as is trying to tease them out of multiple disconnected tools. (The take home message: you need connected tools).

3. Time: Change 11 was one of my favorite MOOCs, but it went on for a long time. My life changed, the semester changes, and I started a number of projects. As a result, I went into lurker mode in the MOOC. While I can see why people may like a long duration MOOC, I myself like MOOCs that are about two-three months in length. It gives you time to get your feet wet and really get involved. It also provides more opportunities to actually build networks.

While I like what I've seen and gotten from #MOOCMOOC, I have to say it feels like a speed dating session. I can barely remember what I commented on today. There are advantages to this (you see and do very quickly, and there is very little chance of burning out as the weeks drag on), but there are disadvantages (namely going so fast you're not sure what you've done).

4. Newsletters: Having daily contact with the MOOC is essential and inspiring. Having something in my email box to remind me about a topic, or better yet, showing me some important threads, is amazingly helpful. Getting an admin note with no content, not so inspiring. With that said, having 10+ messages every day (or every hour in one case) is not so great (I really had to change my notifications on that one). With no newsletters, I feel a little left on my own. With 10+ coming from the facilitator, I feel harassed.

One thing that needs to be emphasized, is that the newsletters are most helpful when it has content or links that help you bring the previous day/week content into focus.

____________________________________________________________________________

If you've read my previous posts, you may have seen that I feel that everyone can adapt the foundations of MOOCs to their own situations and audience. Most of my courses are for undergraduates, and as such, they are not ready for what is seen by many as a MOOC (they are not ready to self-organize). My comments here are a reflection of what I like when I join a MOOC. What I do in my classes is different because my audience is different. If I were to do an open course dealing with an audience use to self-actualized learning (what we're doing in #MOOCMOOC), then my interactions and framework would be different.

What is a MOOC?

Today's topic in #MOOCMOOC is "What is a MOOC?" There are some collabrative documents being worked on to answer that question, to which I have commented, but I realized that I needed to take a moment to really think about the question myself.

To answer the question, a MOOC is inspiration.

Huh? It is a learning opportunity that a person accepts, and then they are inspired to chart their own path to knowledge. The best MOOCs I've participated in have been able to inspire me to explore, read and write (even if it notes to myself). The worst one inspired me to leave (I hate being talked at...as opposed to having a conversation with).

The concept of the MOOC is also inspiring, and that is what I love about it. George Siemens, Stephen Downes and Dave Cormier have each done an amazing job building the foundation of what we see today as MOOCs (specifically connectivist MOOCs). These foundations are then available for us to use, reuse, remix and adapt.